Tom Lechner is an art teacher, IT expert, photographer, facilities manager and role model. He’s also the one who makes sure dozens of homeless children get to school each day. C

Tom Lechner is also the transportation coordinator at Community Transitional School in Portland. The private, nonprofit school for children experiencing homelessness serves about 80 students per day – this year 221 students total from 121 families.

Tom Lechner sits at a schoolroom-style desk in one corner of a busy office, a computer screen in front of him, folders of paperwork on the desk, pen in hand, phone at the ready. He’s a tall, slim guy with tightly curling black hair showing wisps of gray, and frameless glasses perched on his nose. It’s his job to get 80 elementary school children to school every day, no matter where they may have spent the night.

As transportation coordinator, Tom is crucial to the Community Transitional School on Northeast Killingsworth Street. The CTS serves one special sector of the metro area’s population of school-age children: All of the students are homeless. They live in cheap motels or doubled-up in the apartments of relatives or friends; they sleep in shelters or in family cars or outside, on the street. Some students might be in the school for just a day; others have stayed for years. The average length of stay is 13 weeks.

CTS takes care of these complexities one family at a time, wherever they are. How do they do it? Size and intimacy explain a lot. It’s a small, close-knit school; everyone knows everyone. They don’t have to follow each federal guideline. They can be in touch with every family, answer every call.

And they have Tom. He had no experience with homeless people before coming to CTS. But, he said, “I always had this urge to do something that had some sort of good mission to it.”

He’s been touched by seeing the things these kids deal with on a daily basis.

“Sometimes there are circumstances that just stick with you through the evening, and that’s hard.” He looked down and turned his palms up, a small gesture, matter-of-fact.

“I’m a newcomer here,” Tom said, downplaying his role in a way I came to learn was typical. In fact, he’s been running the school’s transportation system for about 10 years.

Before getting the transportation job, Tom was the school’s night janitor. He had been studying physics and math, but at some point, he said, “I noticed I was spending all my time making art, so I dropped out and went off to be an artist.” He graduated from Pacific Northwest College of Art in 1998, and it was tough to find work.

He heard about the janitorial job through friends. “It sounded great, interesting. And part time, so I’d still have time to do art.”

One by one, he acquired other responsibilities. “Whenever they had a computer problem, I’d be just hovering in the background, and I think it was just kind of noticed.” He became – informally – the school’s entire tech department. Then in August 2006, the transportation job opened up, and there he was.

“Every single part of it was difficult,” he said of the early days. “Figuring out all the laws, and then the requirements of the parents. And getting the buses repaired. If it’s just changing lights or something simple, I do it.”

He still makes art, and he’s become the school’s main photographer. Once a week, he teaches a drawing class for a group of lucky students. There are other regular art classes, with all kinds of materials, but in Tom’s class, he said, “we usually just use paper and pencil.” Tom calls it observational drawing, but the kids simply call it Art with Tom.

Tom arrives each morning by bicycle before the buses and settles in at his desk. His first task of the day is to take out the kitchen trash.

He enjoys the diversity of people who come through the doors and interact in the busy, welcoming office: the homeless children and their parents; the dedicated staff and teachers; the many volunteers from all over town, coming in just to help out for a few hours; the neighbors dropping by to donate clothing or school supplies; the high school kids from Lake Oswego who collected breakfast cereal; the big donors bringing a check for a thousand dollars. Everyone becomes part of the team.

What holds this team together is the focus on children. Every CTS student shares the stresses that children with a stable home do not understand – even tease them for. They may be escaping domestic violence, or a parent has lost a job, or there’s been a medical crisis that left the family unable to pay rent. They are all equals in that one important way; no one’s going to put anyone down for where he or she lives. And there are new students every week. It’s one of the benefits, Tom points out: “You’re never the new kid for very long. That’s a great situation.”

Founded in 1990 as part of Portland Public Schools and originally housed at the YWCA downtown, CTS is today a registered private school, an independent nonprofit organization serving homeless children. It’s the only such school in the state. With about 80 students each day – this year 221 students from 121 families – it can reach only a tiny portion of the homeless children in the metropolitan area. But the school does what it can. It operates on a tight budget with a staff of three full-time teachers, one part-time Title I teacher, two teacher’s aides, three office staffers, one meal server, four bus drivers, and many loyal volunteers – all focused on the school’s mission of providing to these children “a place where they have room to learn, laugh with friends and build hope,” according to the school’s website.

Osa outlined the astonishingly simple application process: no birth certificate, no proof of immunization, no paperwork. And no tuition. Families learn of CTS through word of mouth, and the shelters and other support organizations post signs and help spread the word. CTS maintains a close relationship with those in social services; the school depends on these people to help homeless families learn about CTS. A parent calls and gives the child’s name and birth date and most recent grade level, and “in five minutes,” Osa said, “they’re on Tom’s list for the next morning.”

Tom may have to figure out where a family has moved. Once, when parents didn’t call in, Osa told the child, “Find an envelope that has an address on it, and tell us what it says, and then we’ll figure out where to go.” Every day, that second grader read out a new address, and called in to say where she was. She moved 22 times that year. This past year, one student moved 13 times in 110 days, and missed only two days of school.

“Usually I’ll figure out approximately which bus a child should go on and what route,” Tom said, “but that doesn’t always translate into a realistic picture of how things will actually work, and the drivers – sometimes they’ll have to decide what makes sense, which side of the street they can pick up on. If an apartment looks seedy, they might not want to let the kid off until they see a parent there. Or if the kid’s never been there before, he might say, ‘I’m not gettin’ off here!’”

If a child doesn’t show up at the morning bus stop, Tom or someone in the office will call to find out what’s going on – but if they can’t get through and the child doesn’t show up for a couple of days, they stop sending the bus. It’s a painful part of the job: “You get to know the kids, and then they’re gone.”

Osa described what these families deal with: “It’s chaotic, a brutal lifestyle. Outside of school, it’s near-constant instability.”

Once the children arrive at CTS each day, they’re safe, well-fed and cared for. For homeless families, that may seem more important than the education the kids are getting, she said; many of their parents didn’t finish school.

He said that what he should have is buses that never break down, and he’d like to be able to pay drivers better. But he makes do. When a bus does break down on the road and can’t be repaired right there, there’s no back-up bus waiting at school. Tom has to call on local taxi companies to rescue the kids. Yes, it’s expensive, but what else can he do? The kids are depending on him.

“Behind Tom’s desk, there’s a huge pink heart made from construction paper. It’s decorated with messages, in children’s practiced handwriting – a list of words to describe Tom: happy, clever, good artist

(“Without you, I wouldn’t have known what shading is”), good with computers, helpful, organized, brave, “helps us with our math problems,” “has a big job.” And thank-you notes: Thank you for the keys to the bathroom. Thank you for lifting the tables at lunchtime, for driving the bus, for bringing color into our lives. And one last note: The unsung hero of CTS.

Tom dismisses any talk of his own ccomplishments and puts it all on the children. He doesn’t get them to school, he insists; they do it.

“A lot depends on the kids’ initiative,” he said. “They have to figure it out. Somehow, magically, they find a way to get here.” It’s a remarkable place, and magic doesn’t seem too strong a word. What would Tom most want others to know about the Community Transitional

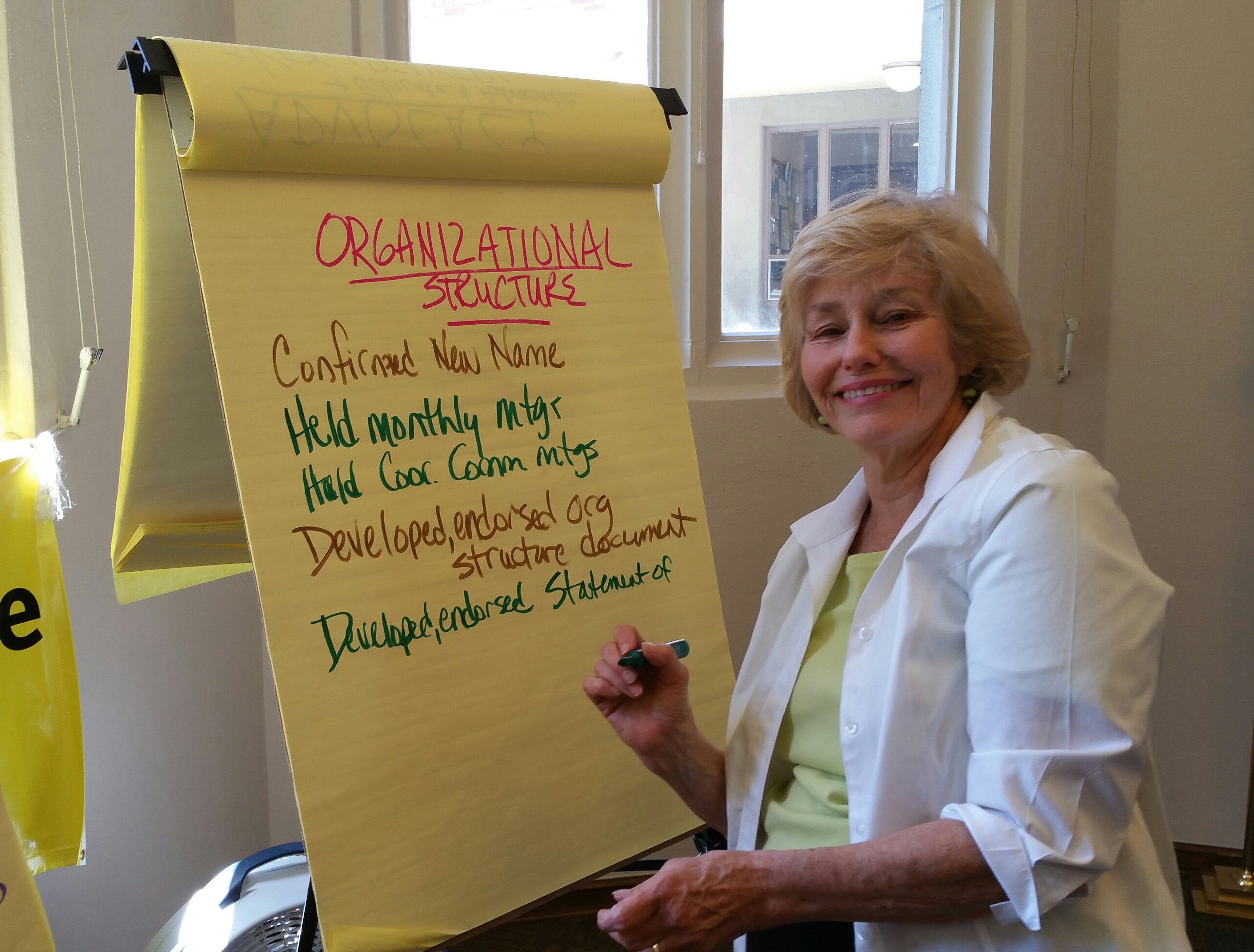

Hundreds of Street Roots supporters gathered at the Portland Convention Center on October 5, 2017, including several members of the Interfaith Alliance on Poverty. Shown above are Tom Hering, Rose City Presbyterian Church, Dave Albertine, the Madeleine Catholic Parish, Holly Schmidt, Westminster Presbyterian Church, Carol Turner, Westminster Presbyterian Church, and Sarabelle Hitchner, First Unitarian Church.

Hundreds of Street Roots supporters gathered at the Portland Convention Center on October 5, 2017, including several members of the Interfaith Alliance on Poverty. Shown above are Tom Hering, Rose City Presbyterian Church, Dave Albertine, the Madeleine Catholic Parish, Holly Schmidt, Westminster Presbyterian Church, Carol Turner, Westminster Presbyterian Church, and Sarabelle Hitchner, First Unitarian Church. Street Roots Newspaper Seller, Lori Lematta, and Executive Director, Israel Bayer

Street Roots Newspaper Seller, Lori Lematta, and Executive Director, Israel Bayer Jessica’s family was poor. They endured the challenges confronted by poor people around the world, struggling to find work, food, and shelter. She also learned that real wealth is found not in accumulation of possessions, but in the relationships we forge within our families and communities.

Jessica’s family was poor. They endured the challenges confronted by poor people around the world, struggling to find work, food, and shelter. She also learned that real wealth is found not in accumulation of possessions, but in the relationships we forge within our families and communities.